Give me Kurosawa and Tarkovsky

and I'll watch movies until my eyes fall out of their sockets (part 2)

So I was at the Fine Arts college and I think the class was supposed to be observation drawing, but the teacher, called Fábio Noronha, decided to do something different: we would watch Tarkovsky’s Stalker. Here I’m talking about events from the previous millennium, so it was a rented VHS that looked like a derelict object saved from a flood - which is a very Tarkovsky thing.

And, as frequently happens, the teacher was right: few things have done so much for my drawing and aesthetic formation in general than Stalker and other works by our friend Andrei - so, thank you, Noronha! After that, the regular revisiting of Tarkovsky’s movies turned into some sort of celebratory and surviving ritual and Sculpting In Time gained the sacred book status. Unlike Tarkovsky, I’m not a spiritual person, so let’s say that it’s an aesthetic, philosophical and humanist kick.

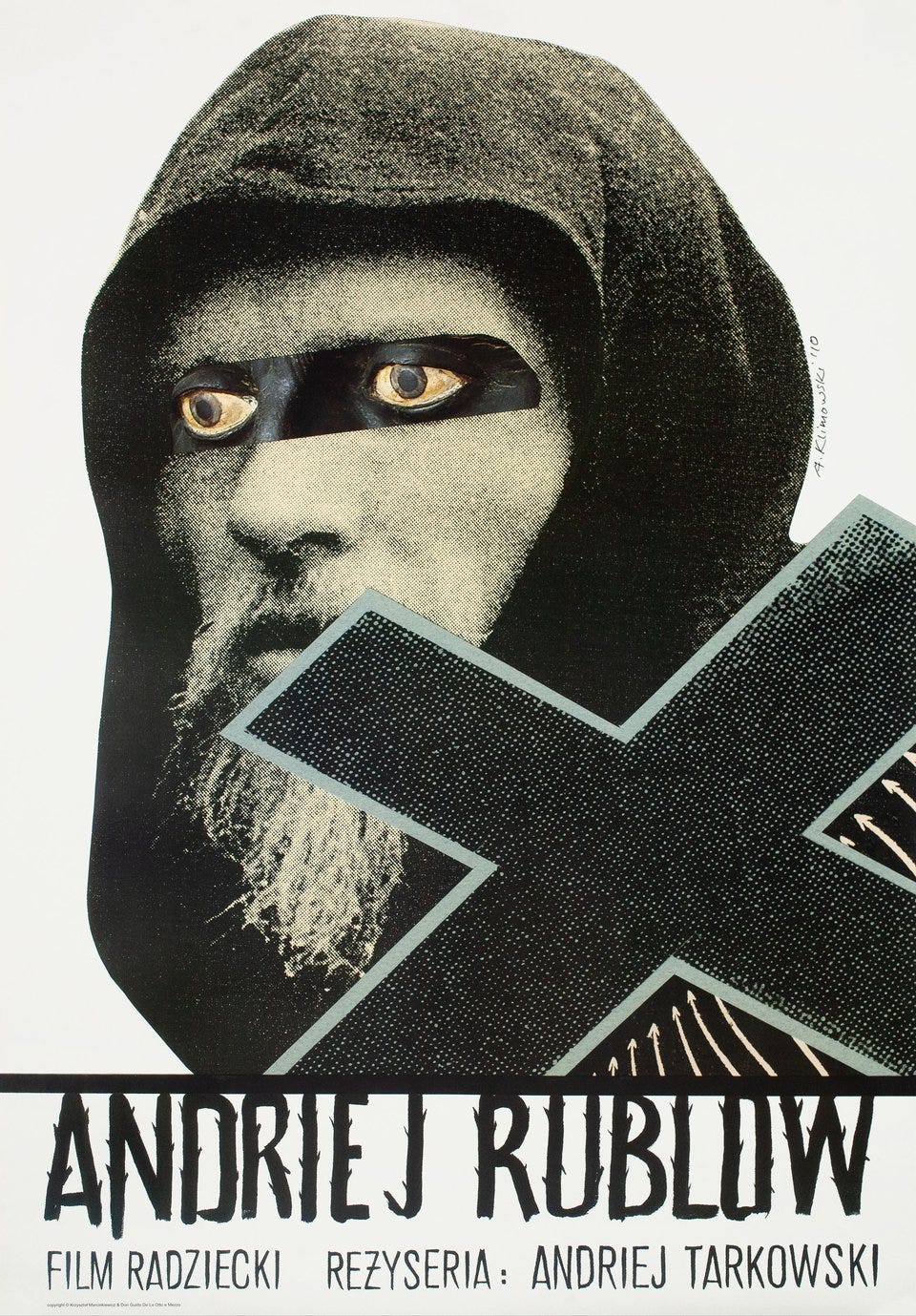

Andrei Rublev is crucial for my motivation and intentions in La Grande Crociata - the presentation of external and inner conflicts; the role of nature; faith not as absolute certainy, but as an enclosure for ambiguity and doubt; Rublev as an artist dealing with power structures beyond his reach: the church, the aristocracy, a foreign army invading his land, the belief system itself, all of this topped with his questioning of his own capabilities as a worker in the religious icon business.

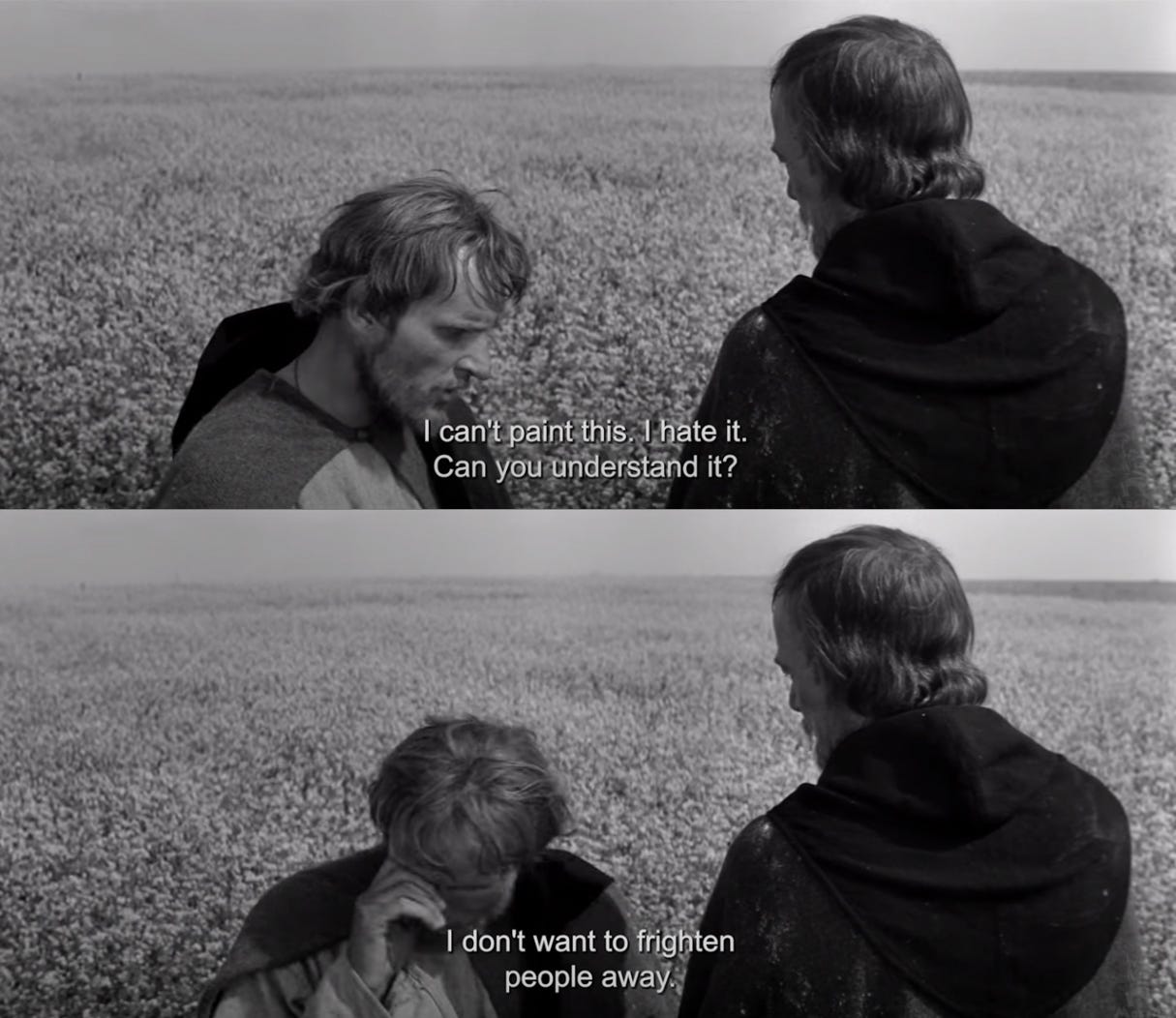

Loosely based on the life of the not only famous but officially declared saint Andrei Rublev - the guy even has a site with his portfolio - the movie is divided into eight episodes and they’re not centered only on Rublev, but in the struggles of other characters in the 1400s, a busy time in Russia. If someone tells you that Tarkovsky’s movies are slow, boring and nothing happens, slap the rascal in the face and tie firmly the silly person on a chair to watch Andrei Rublev: it starts with a dude flying on a balloon in 1400, it has pagan rituals, a tatar invasion, sword fights, arrows, horses, dogs, fire, Rublev refusing to paint a representation of the Judgement Day. What else do you want, an orthodox christian car chase?!

The last episode is about the making of a goddamn bell, a huge one, but the bellmaker is dead and his young son takes the commission - this episode is an overwhelmingly hard, Herzog style, journey that echoes in my head everytime I hear a bell.

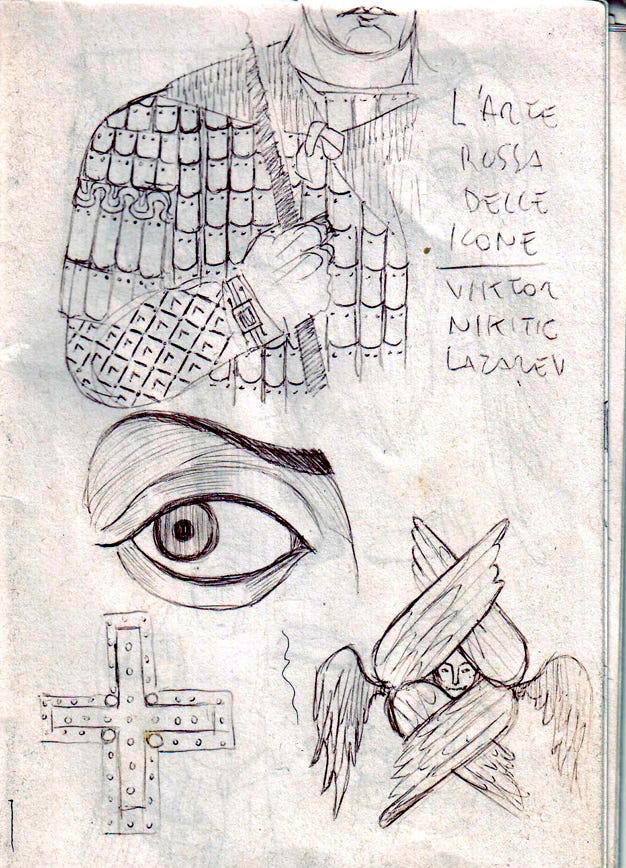

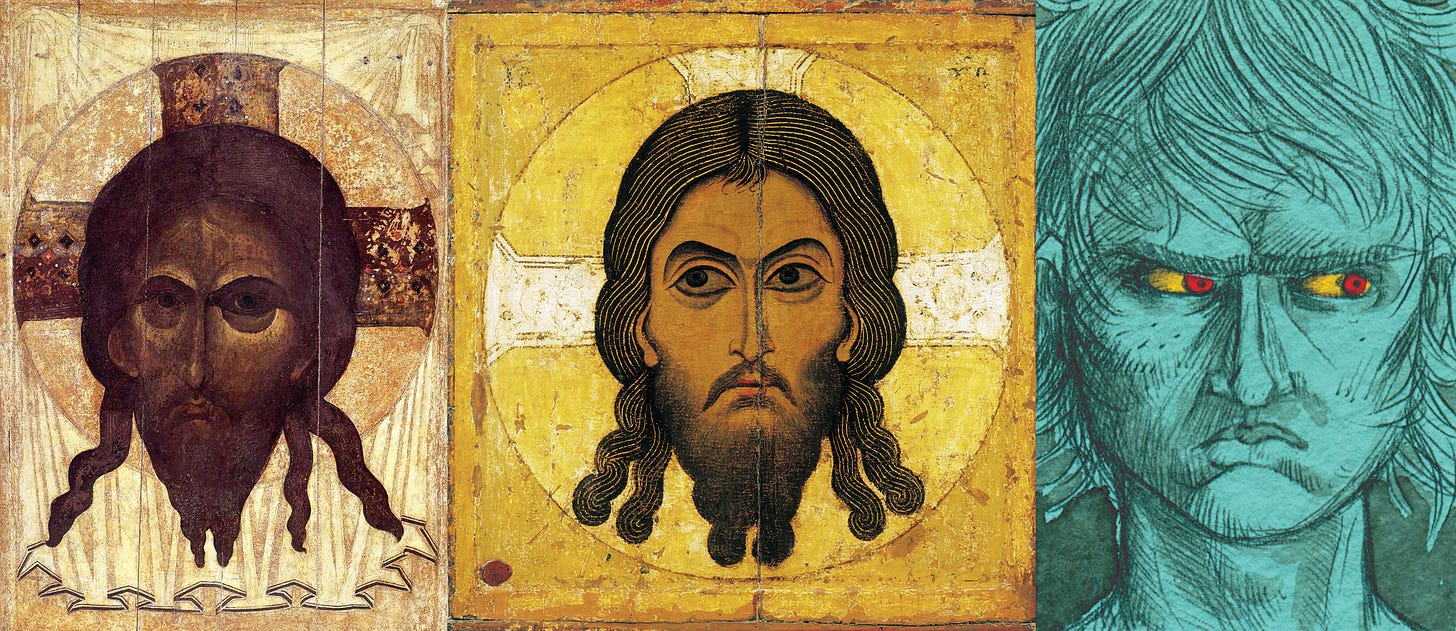

I get as reference and inspiration not only the movie about Rublev, but his work and orthodox christian icons in general. Here in Cagliari I live next to the Biblioteca Emilio Lussu, a public library, and this beautiful and gentle institution has an amazing Viktor Lazarev’s book dedicated to russian icons - and sure as the rain in a Tarkovsky movie, I visited the book a few times and made some sketches to use as reference in my comic.

In his writings Tarkovsky poses the question: what can be done only through cinema? In doing comics, we must approach the task in the same way: what can be done only through comics instead of through novels, movies, theater? How the choosing of this vocabulary, this set of tools and codes, can be justified and be relevant to our personal and collective experiences in storytelling? In a wider scope, how can it be important to the human experience?

I leave you with such practical and existential questions echoing like huge bells until next week, when we’ll probably share more doubts than certainties. Isn't it formidable?